(This is a huge project for me, since some details are even confusing for myself, I’m still a beginner of this field, this blog will be innovated inconstantly. It’s all up to my mood ^_^.)

This is an introductory article to a famous problem appeared in the Hamiltonian Dynamical Systems (and Symplectic topology), the Arnold conjecture, and a brief idea, which originated from Andreas Floer, to prove this conjecture. Let’s first start from the Morse theory.

1 Morse Homology

1.1 General Idea of Marston Morse

From a nowadays perspective of the geometry (probably due to Grothendieck and Serre), studying the geometry of a space (scheme, variety, manifold, etc.) is equivalent to study the structural sheaf of that space

, in a mjority of the case, that structural sheaf is constructed from analytical aspects, for example, if

is a smooth manifold, it can be completely determined by its ring (or algebra) of smooth functions on

, namely

, that is to say, the restriction in doing analysis on

is completely due to the geometrical nature of

.

Morse theory is a prior example of this philosophy. Morse’ idea was wishing to use a “Nice” function defined on a smooth manifold

to encode with some certain geometrical or topological properties of

, these nice functions are so called the Morse functions, that is a smooth function

with nondegenerate critical points, for example, the height function of a closed surface:

It is proved that Morse functions are vastly existed on every compact manifold, hence it is a great tool that can help with the investigation of the topology of that manifold, a well-known application is that a critical point of a Morse function corresponds to a cellular structure of the underlying manifold.

Near each critical point of

, there is a so-called Morse chart

such that the expression of

under this chart is simply a quadratic form:

The negative index of this quadratic form is called the index of this critical point (index is a nonnegative integer), denoted by

and it is independent of the choice of the Morse charts. Again, as the figure shows above, the critical point

has index 0, and

has index 1.

There is also another (more intuitively) way to find the index of a critical point.

If we impose a Riemannian structure on

, then we can define the gradient vector field

of a Morse function

in the following way: for any

and

:

the field will induce a flow

on

, and if we fix a point

, the flow acting on this point defines a curve

, this curve is called the gradient flow line of

(hence the flow line flows through a point is uniquely determined), one can show by definition that the function

decreases along the minus gradient flow line:

And the critical points of the Morse function are the singularities (zeros) of the gradient field

. There are two natural definitions arising from here:

They are called the stable and unstable (sub)manifold of the critical point respectively, intuitively, the stable submanifold consists of the points in

which will flow to

along the gradient flow line, and in contrast, the unstable submanifold consists of the points which be flowed from

. For example, for the height function of

as illustrated above, the stable submanifold for north pole

is

, and the unstable one is

, now it is not hard to prove (but still challenging for a beginner) the following result:

Theorem 1.1: are open submanifolds of

and they are diffeomorphic to open disks, moreover:

More precisely, the unstable submanifold implies a

cell inside

.

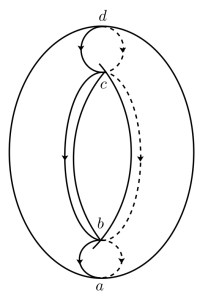

As another example, the following figure shows the critical points of the height function on a torus , it has 4 critical points

,

is the complement of the line ending at

.

Also, it is not hard to find the gradient flow line flows from high index critical point to the low index one.

1.2 Morse Complex

Although, we know from the homological axiom that all homologies must be equal, but it is still necessary to construct homology functor from different aspects, for they offer us various ways in the comprehension of the object, the simplicial homology came through the simplicial decomposition, the de Rham cohomology came through the analysis on manifold, however, the Morse homology is constructed through a view from dynamical system.

We define the th Morse chain group as:

That is a free -module generated by the critical points of

with index

.

In order to define the boundary map, we need to find the connection between the critical points in successive indices, however, we need to impose an extra hypothesis.

We call a gradient field satisfies the Smale condition if for any two critical points

of

,

intersects transversally with

, denoted by

, once if a gradient field satisfies with the Smale condition, one has:

We denote by of this intersection, it consists of all points flow (along the gradient flow lines) from

to

:

The Lie group acts by translation (along gradient flow lines) on

, that is

, and it is free precisely if

, hence we obtained a quotient space

, it consists of all gradient flow lines connecting

and

, and we have for its dimension (a smooth manifold since by free Lie group action):

So now, if two critical points are of successive indices, then is a discrete manifold, hence we can define

to be its cardinality modulo 2, and here comes the boundary map:

It is pretty not easy to show that:

Theorem 1.2: The following is a chain complex:

Hence it determines a homology group in coefficient

, and it is independent of choice of the Morse function

.

This homology group is called the Morse homology. Notice that, if we impose an orientation on , we can also use the

coefficient, however, we still prefer the

coefficient since it is a field, hence we can talk about the dimension of the vector space

.

It can be proved that the Morse homology has functoriality, hence it has all properties of other homologies, for example, Künneth formula, Poincaré duality, homotopy invariance, etc. Moreover, it is no wonder that the Morse homology coincide with the cellular homology, i.e., there is a natural isomorphism between these two chain complexes.

What a surprising result of the Morse homology is that it can help to evaluate the number of the critical points of a Morse function.

Theorem 1.3 (Morse Inequality): The number of critical points of a Morse function on a manifold

is at least the sum of dimensions of all homology groups, i.e.:

Proof: It is obviously that:

Now, it is appropriate to end the story of Morse theory, right now.

2 Hamiltonian Dynamics

2.1 Hamiltonian Equations

Now we assume our to be a compact symplectic manifold of dimension

. For a smooth (Hamilton) function

, there is a “symplectic analogue” of the gradient vector field, called the Hamiltonian vector field

associated to the function

:

for all , it can also be denoted by

, and likewise, the critical points of

are exactly the singularities (zeros) of Hamiltonian

.

The relationship between Hamiltonian vector field and the gradient vector field is subtle. Recall that there is a compatible almost complex structure on every symplectic manifold, that is a smooth family of linear isomorphisms

, with

, and satisfies with the compatible condition:

and is a Riemannian metric, for all

. Through a brief calculation we can find that

So, the Hamiltonian field is just a “twisted” gradient field.

The flow of a Hamiltonian is given by the ode:

If we write down in a local Darboux chart , then that ode is just the Hamiltonian equation in Mechanics. Indeed, we can choose a calibrated almost complex structure at each

with the standard matrix representation (under the base

):

and assume , hence our ode becomes to:

The flow of the Hamiltonian

is called the Hamiltonian flow, to be distinguished, we shall write this as

, physicists prefer to call this a conservative current, since the Hamilton function

is a constant along the Hamiltonian flow:

, for some

.

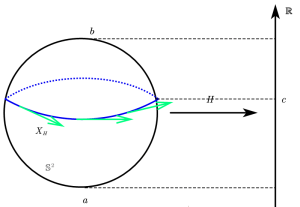

As a simple example, one can consider the height function (again!) on

, the Hamiltonian vector field

is the tangent field of the weft circle, its Hamiltonian flow is just the weft, which is the level set

at the height

. (Comparing with the gradient flows, they are meridians.)

Like the case in the gradient flow (it preserves the Riemannian structure), the Hamiltonian flow preserves the symplectic structure, that is , a symplectomorphism. Also, we shall note that the critical points are exactly the fixed points of the one parameter Lie group

.

2.2 Periodic Solutions

There is a significant concept in Hamiltonian dynamical systems, that is the periodic orbits/solutions of a Hamiltonian system. An orbit (or I shall say, the Hamiltonian flow line) of the Hamiltonian flow is called a periodic orbit (of periodic 1) if

, geometrically, a periodic orbit looks likes some unions of

(The wefts of a sphere for instance).

It is obviously that the critical points of are all periodic-1 orbits of the associated Hamiltonian dynamical system, since the orbits of critical points are just a single point, they are identically periodic, and of course, if

is a periodic orbit of periodic 1, then every point in the Hamiltonian flow line is a fixed point of

.

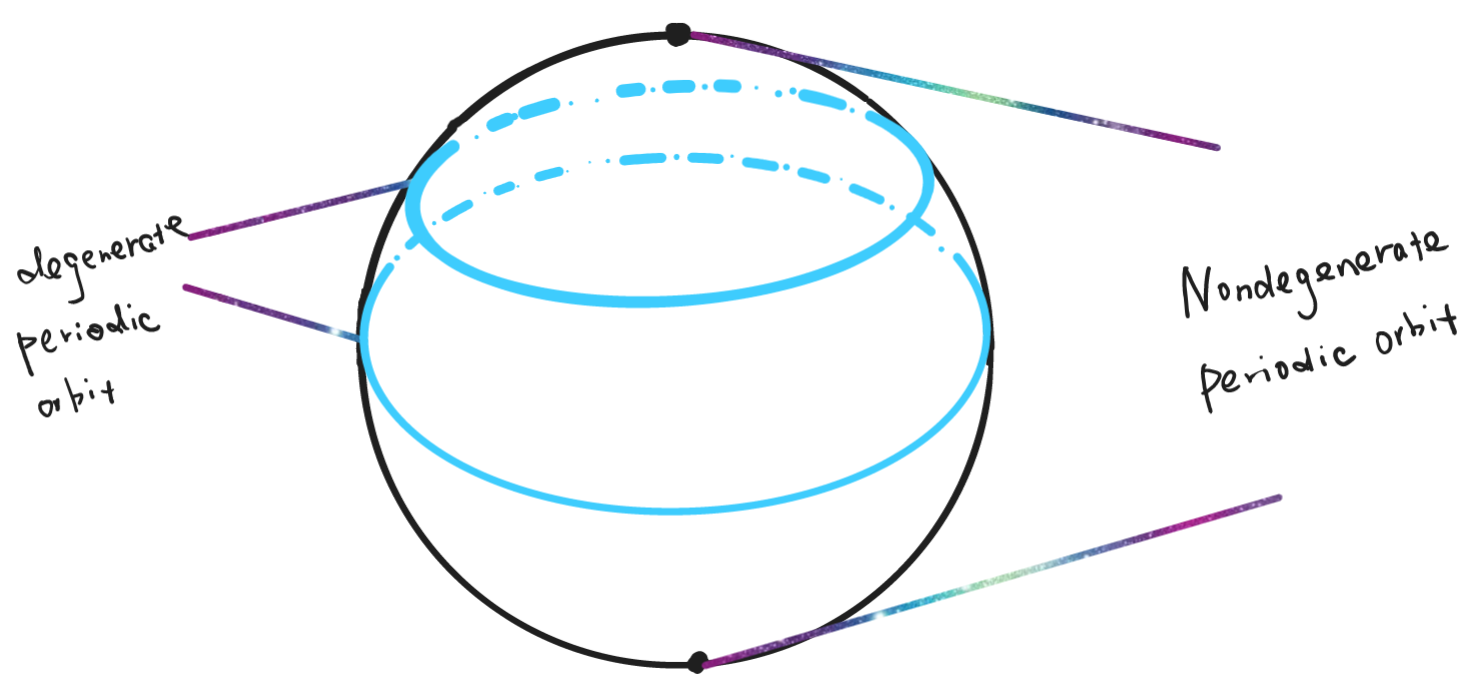

As an analogue in Morse theory, we can also define what is a nondegenerate periodic orbit.

Definition 2.1: A periodic orbit (of periodic 1) is nondegenerate, if the differential map

does not have 1 as an eigenvalue.

Intuitively, the nondegeneracy of a periodic orbit requires the orbit cannot be “too large”, for if so, we have the subspace is the eigensubspace subordinate to the eigenvalue 1 of

.

The relation between nondegenerate periodic orbits and nondegenerate critical points is a little subtle:

Theorem 2.1: If a critical point of corresponds to a nondegenerate periodic-1 orbit of

, then it is a nondegenerate critical point. Moreover, if the Hamilton function

is sufficiently “

small”, namely, the norm of its Hessian is less than

, then vice versa.

Proof: For the first statement, by definition, we have for all

where denotes the vector field extended by

, if we can show for all

,

, then by the nondegeneracy of

, the result will be shown.

Indeed, we choose to be a critical point of

corresponding to a periodic orbit of

of periodic 1, since

, and

, hence there exists some

such that

, however, this is

, as was to be shown.

For the second statement, if we use the local coordinates, the matrix of is the Jacobian, and we have

where choose to be a standard calibrated almost complex structure, so, if the norm of

is no more than

, it is obviously nondegenerate.

The existence of periodic orbits is a core and hard question in Hamiltonian dynamical systems, there is a big conjecture associate to this question, which conjectures the lower bound of the number of nondegenerate periodic orbits of a certain Hamiltonian system, that is the Arnold conjecture.

3 From Morse to Arnold

One of the reasons why I want to write this blog is that I want to make us sure why Arnold conjectured so, instead of conjecturing something others. If we know why it may true, this will give us an appropriate motivation to learn the forthcoming materials, such as Floer homology, Maslov index, Fredholm theory, etc.

Combining with section 2.2 and Morse inequality (theorem 1.3), we have the following simple corollary:

Theorem 3.1: We assume all periodic-1 orbits of a Hamiltonian are nondegenerate, then the number of such periodic orbits of the Hamiltonian system on compact symplectic manifold

is greater than

.

Here, our Hamiltonian dynamical system is an autonomous system, which means does not depend on the time, however, people will care more about the nonautonomous systems, that is to consider a time dependent Hamilton function:

, then the Hamilton equation becomes into:

V.I.Arnold conjectured the following:

Conjecture 3.2 (Hamiltonian Arnold Conjecture): We assume all periodic-1 orbits of a nonautonomous Hamiltonian are nondegenerate, then the number of all such periodic orbits is at least

.

There is also another more topological version of Arnold conjecture, called the Lagrangian intersection Arnold conjecture:

Conjecture 3.3 (Lagrangian Intersection Arnold Conjecture): Suppose is a compact symplectic manifold,

is a Lagrangian submanifold, then for any Lagrangian

which Hamiltonian isotopic and intersects transversally to

, then the intersection number:

The conjecture 3.3 implies the conjecture 3.2, however, the Lagrangian intersection one will not be considered in this blog.

Just one more remark about Arnold conjecture 3.2, that is the Hamiltonian can be assumed to be periodic-1, too. Which is

Theorem 3.4 For any non-autonomous Hamiltonian systems we can associate it with a new Hamiltonian

with

and

.

Proof Let be a bump function onto

and with compact support on

, let

, notice that

It is obviously that . Let

, it is clearly that

is the flow of the Hamiltonian associated to

, and

can be extended to be periodic-1.

Many mathematicians made their efforts to solve these conjures, it was Andreas Floer who developed a method, called the Floer homology, which is an analogue of the Morse theory in infinite dimensional, and proved both conjectures, the later one is so called the Lagrangian intersection Floer homology. Meanwhile, there are a lot of “particular” version of the Arnold conjecture which can be proved via different theories, for example, Tamarkin and some other mathematicians used the “micro-local sheaf theory” proved the Lagrangian intersection Arnold conjecture for the cotangent bundle !

Next, we will talk about the Floer homology originated from the Hamiltonian dynamical case.

4. An Approach of Andreas Floer

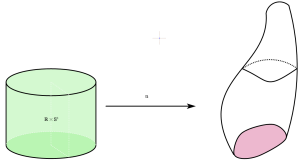

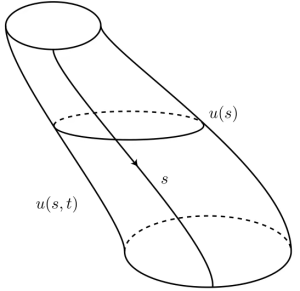

Since we are focusing on the “loops” inside a symplectic manifold , we can consider the space of loops instead of the manifold itself, hence we can define

This space endows with a topology (open-compact), however, it is not even connected since two non-homotopical loops are lying in different connected components, but our non-degenerate periodic-1 orbits are those homotopical to the trivial ones, so we can the loop space as

Floer’s idea was to do the Morse theory on this loop space , normally, this space is not a finite dimensional manifold but a Banach manifold.

4.1 Loop Space & Action Functional

For loop space , I will not introduce the structure of Banach manifold on it but will introduce the tangent space directly.

For any loop , to compute the tangent space

at this point, we can take tangent vectors as those of curves on

passing through

, that is

, we can take this as the map

with , hence the tangent vectors are just those

, where

. We can see that a tangent vector at

is just a vector field

on

along

, and of course

. We’d better make a convention here:

Convention 4.1: (1). For a curve on we refer to be a map

.

(2). For a tangent vector in , we refer to be a vector field

on

along

, satisfying

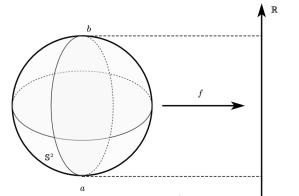

Another important notion is about the action functional, which will play an analogy role in Floer homology as Morse functions play in the Morse homology. Let be a time-dependent Hamiltonian function on a symplectic manifold

, define

to be the action functional on the loop space , where

is the extension of the loop

to the whole disk

.

Obviously, it is not well-defined since the action functional varies as the extension varies, but if we impose an extra condition , then it dose, since we have

where is defined by gluing of

along their common boundary. Later, our symplectic manifolds will be those with this extra condition.

Next, I will compute the tangent map of this action functional.

Theorem 4.1: We have the tangent map of the action functional:

Proof. To compute the tangent map, we choose a path on

, as we discussed before, and passing through

at time

, and with tangent

, to be simplified we will denote this path by

, and its extension to

will still be denoted by

if there are no ambiguities.

Now, by definition we have:

For first term, by chain rules we have

For second term, by applying Cartan’s magic formula, we have

Combining with all these results, we gain the desired formula, cool!

Now, it is not hard to find the relationship between nondegenerate periodic-1 orbits and critical points of the action functional :

Theorem 4.2 A loop is a non-degenerate periodic-1 orbit of

if and only if it is a critical point of the action functional

.

So now, we shall be awarded of what we need to play Morse theory on this action functional, here is the table of “menu”:

| Morse Theory | Floer Theory |

| Finite dimensional Manifold | Banach manifold |

| Morse function | Action functional |

| Critical points of | Critical “loops” of |

| Morse index of critical points | Maslov index of critical “loops” |

| Equation of gradient flow | Floer equation |

| Counting flow lines connecting two critical points with successive index | Counting the number of solutions to Floer equation |

| Morse homology | Floer homology |

Next, I will introduce those analogously notions in Floer theory

4.2 Flow Lines Connecting Two Critical Points

Since for now, the periodic orbits are all critical points of the action functional, just as what we have done in Morse homology, we need to investigate the flow lines connecting them, we first start from the gradient of the action functional.

There is an -tamed Riemannian structure on the symplectic manifold

, namely

for all , and

is the calibrated almost complex structure, hence it induces a Riemannian structure on

, just as we’ve mentioned before, for any

:

Now it allows us to define the gradient vector field :

Combining with theorem 4.1, we have

Theorem 4.3: We have

Now we can compute the flow line of the minus gradient field, let be a curve (cf. convention 4.1) in

, it satisfies with the minus gradient field

, hence

This equation is called Floer equation, notice that Floer equation is very similar to Cauchy-Riemann equation, since the first 2 terms is just Cauchy-Riemann equation, with a gradient of redundant.

Recall that we only care about those smooth contractible and periodic-1 solutions in . Also note that, we didn’t know whether Floer equation has a solution yet.

……

Next, we will introduce the index of these critical “loops”, they are materials to make Floer chain groups, and how to count the number of the solutions of Floer equation, they are materials to make Floer boundary map.

5 Reference

- Michèle Audin, Morse Theory and Floer Homology, Springer-Verlag.

- V.I. Arnold, On a Topological Property of Globally Canonical Maps in Classical Mechanics, 1965

- C. Viterbo, An Introduction to Symplectic Topology Through Sheaf Theory